If One Strand of Dna Molecule Read Accttgac

Biologists in the 1940s had difficulty in accepting DNA as the genetic material because of the apparent simplicity of its chemistry. DNA was known to be a long polymer composed of only four types of subunits, which resemble one another chemically. Early in the 1950s, Dna was first examined by x-ray diffraction analysis, a technique for determining the three-dimensional atomic structure of a molecule (discussed in Chapter viii). The early 10-ray diffraction results indicated that DNA was composed of two strands of the polymer wound into a helix. The observation that DNA was double-stranded was of crucial significance and provided one of the major clues that led to the Watson-Crick structure of Dna. Only when this model was proposed did Dna'southward potential for replication and information encoding go apparent. In this department nosotros examine the structure of the Dna molecule and explain in general terms how it is able to shop hereditary information.

A DNA Molecule Consists of Ii Complementary Chains of Nucleotides

A DNA molecule consists of two long polynucleotide chains equanimous of four types of nucleotide subunits. Each of these bondage is known as a Deoxyribonucleic acid chain, or a DNA strand. Hydrogen bonds between the base portions of the nucleotides concord the two chains together (Figure four-three). Equally nosotros saw in Chapter 2 (Panel 2-half-dozen, pp. 120-121), nucleotides are composed of a five-carbon sugar to which are fastened i or more phosphate groups and a nitrogen-containing base. In the example of the nucleotides in DNA, the sugar is deoxyribose fastened to a unmarried phosphate group (hence the name deoxyribonucleic acid), and the base may be either adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), or thymine (T). The nucleotides are covalently linked together in a chain through the sugars and phosphates, which thus form a "backbone" of alternating saccharide-phosphate-saccharide-phosphate (see Figure 4-3). Because only the base differs in each of the four types of subunits, each polynucleotide chain in DNA is analogous to a necklace (the backbone) strung with four types of beads (the four bases A, C, Grand, and T). These same symbols (A, C, G, and T) are also commonly used to denote the four different nucleotides—that is, the bases with their attached carbohydrate and phosphate groups.

Figure 4-three

Dna and its edifice blocks. Dna is fabricated of four types of nucleotides, which are linked covalently into a polynucleotide chain (a Dna strand) with a sugar-phosphate backbone from which the bases (A, C, G, and T) extend. A Deoxyribonucleic acid molecule is composed of ii (more than...)

The fashion in which the nucleotide subunits are lined together gives a DNA strand a chemic polarity. If we think of each carbohydrate every bit a cake with a protruding knob (the v′ phosphate) on one side and a hole (the 3′ hydroxyl) on the other (meet Figure 4-3), each completed chain, formed by interlocking knobs with holes, volition have all of its subunits lined up in the same orientation. Moreover, the two ends of the concatenation volition be easily distinguishable, every bit i has a hole (the 3′ hydroxyl) and the other a knob (the 5′ phosphate) at its terminus. This polarity in a Deoxyribonucleic acid chain is indicated by referring to 1 end as the iii′ end and the other as the v′ finish.

The three-dimensional structure of Dna—the double helix—arises from the chemic and structural features of its two polynucleotide bondage. Because these two bondage are held together by hydrogen bonding between the bases on the different strands, all the bases are on the inside of the double helix, and the sugar-phosphate backbones are on the outside (encounter Figure 4-three). In each instance, a bulkier ii-band base (a purine; encounter Panel two-six, pp. 120–121) is paired with a unmarried-ring base (a pyrimidine); A always pairs with T, and Thou with C (Effigy four-4). This complementary base of operations-pairing enables the base of operations pairs to be packed in the energetically most favorable organisation in the interior of the double helix. In this arrangement, each base pair is of like width, thus belongings the sugar-phosphate backbones an equal distance apart forth the Deoxyribonucleic acid molecule. To maximize the efficiency of base-pair packing, the 2 sugar-phosphate backbones air current around each other to grade a double helix, with ane complete turn every ten base pairs (Figure four-5).

Figure 4-4

Complementary base pairs in the DNA double helix. The shapes and chemical structure of the bases allow hydrogen bonds to form efficiently only between A and T and between Yard and C, where atoms that are able to class hydrogen bonds (see Panel 2-3, pp. 114–115) (more...)

Figure 4-5

The Dna double helix. (A) A infinite-filling model of one.v turns of the DNA double helix. Each turn of DNA is made up of ten.4 nucleotide pairs and the center-to-center distance between adjacent nucleotide pairs is 3.four nm. The coiling of the two strands around (more...)

The members of each base of operations pair can fit together inside the double helix merely if the two strands of the helix are antiparallel—that is, only if the polarity of one strand is oriented reverse to that of the other strand (see Figures iv-3 and 4-4). A outcome of these base-pairing requirements is that each strand of a DNA molecule contains a sequence of nucleotides that is exactly complementary to the nucleotide sequence of its partner strand.

The Structure of DNA Provides a Mechanism for Heredity

Genes carry biological information that must be copied accurately for transmission to the next generation each time a prison cell divides to form two daughter cells. Two central biological questions arise from these requirements: how tin the information for specifying an organism exist carried in chemical grade, and how is it accurately copied? The discovery of the structure of the Dna double helix was a landmark in twentieth-century biology because it immediately suggested answers to both questions, thereby resolving at the molecular level the trouble of heredity. Nosotros discuss briefly the answers to these questions in this section, and we shall examine them in more detail in subsequent chapters.

DNA encodes data through the order, or sequence, of the nucleotides along each strand. Each base—A, C, T, or Yard—tin can be considered as a letter in a four-letter of the alphabet alphabet that spells out biological messages in the chemical structure of the Deoxyribonucleic acid. Every bit we saw in Affiliate 1, organisms differ from one another because their respective Dna molecules accept different nucleotide sequences and, consequently, acquit different biological messages. But how is the nucleotide alphabet used to make messages, and what practice they spell out?

Equally discussed above, it was known well before the structure of DNA was determined that genes contain the instructions for producing proteins. The DNA messages must therefore somehow encode proteins (Effigy 4-six). This relationship immediately makes the problem easier to understand, because of the chemic graphic symbol of proteins. As discussed in Chapter 3, the properties of a poly peptide, which are responsible for its biological role, are determined by its three-dimensional structure, and its structure is adamant in plough by the linear sequence of the amino acids of which it is composed. The linear sequence of nucleotides in a gene must therefore somehow spell out the linear sequence of amino acids in a protein. The exact correspondence betwixt the iv-letter nucleotide alphabet of Deoxyribonucleic acid and the xx-letter amino acid alphabet of proteins—the genetic code—is not obvious from the Deoxyribonucleic acid structure, and information technology took over a decade afterward the discovery of the double helix before it was worked out. In Chapter 6 we depict this code in item in the course of elaborating the process, known equally gene expression, through which a cell translates the nucleotide sequence of a gene into the amino acid sequence of a protein.

Figure four-6

The relationship betwixt genetic data carried in Dna and proteins.

The complete set of information in an organism's DNA is called its genome, and it carries the information for all the proteins the organism will always synthesize. (The term genome is also used to describe the Deoxyribonucleic acid that carries this data.) The amount of information contained in genomes is staggering: for example, a typical man cell contains 2 meters of Dna. Written out in the 4-letter nucleotide alphabet, the nucleotide sequence of a very pocket-sized human gene occupies a quarter of a page of text (Figure 4-7), while the complete sequence of nucleotides in the human genome would fill more than a thousand books the size of this one. In improver to other disquisitional information, it carries the instructions for about 30,000 singled-out proteins.

Figure 4-7

The nucleotide sequence of the homo β-globin gene. This gene carries the information for the amino acid sequence of one of the ii types of subunits of the hemoglobin molecule, which carries oxygen in the blood. A different factor, the α-globin (more...)

At each jail cell division, the cell must copy its genome to pass it to both daughter cells. The discovery of the structure of DNA besides revealed the principle that makes this copying possible: because each strand of DNA contains a sequence of nucleotides that is exactly complementary to the nucleotide sequence of its partner strand, each strand can deed as a template, or mold, for the synthesis of a new complementary strand. In other words, if nosotros designate the two DNA strands as S and S′, strand S can serve every bit a template for making a new strand S′, while strand Due south′ can serve as a template for making a new strand S (Figure 4-eight). Thus, the genetic data in DNA can be accurately copied past the beautifully simple process in which strand South separates from strand S′, and each separated strand then serves equally a template for the product of a new complementary partner strand that is identical to its former partner.

Figure 4-8

Deoxyribonucleic acid as a template for its ain duplication. As the nucleotide A successfully pairs only with T, and G with C, each strand of Deoxyribonucleic acid can specify the sequence of nucleotides in its complementary strand. In this way, double-helical Dna can be copied precisely. (more...)

The ability of each strand of a DNA molecule to act equally a template for producing a complementary strand enables a cell to copy, or replicate, its genes before passing them on to its descendants. In the next chapter nosotros draw the elegant machinery the prison cell uses to perform this enormous task.

In Eucaryotes, DNA Is Enclosed in a Cell Nucleus

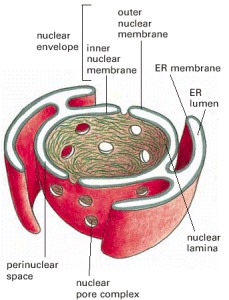

Nearly all the Dna in a eucaryotic cell is sequestered in a nucleus, which occupies about 10% of the total cell volume. This compartment is delimited by a nuclear envelope formed by two concentric lipid bilayer membranes that are punctured at intervals past large nuclear pores, which transport molecules between the nucleus and the cytosol. The nuclear envelope is direct connected to the extensive membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum. It is mechanically supported by ii networks of intermediate filaments: 1, called the nuclear lamina, forms a thin sheetlike meshwork inside the nucleus, merely below the inner nuclear membrane; the other surrounds the outer nuclear membrane and is less regularly organized (Effigy 4-9).

Figure 4-9

A cross-sectional view of a typical prison cell nucleus. The nuclear envelope consists of 2 membranes, the outer one being continuous with the endoplasmic reticulum membrane (run into also Figure 12-9). The space inside the endoplasmic reticulum (the ER lumen) (more...)

The nuclear envelope allows the many proteins that human action on DNA to be full-bodied where they are needed in the cell, and, equally nosotros meet in subsequent capacity, it also keeps nuclear and cytosolic enzymes separate, a feature that is crucial for the proper functioning of eucaryotic cells. Compartmentalization, of which the nucleus is an example, is an important principle of biology; it serves to constitute an surround in which biochemical reactions are facilitated by the high concentration of both substrates and the enzymes that act on them.

Summary

Genetic information is carried in the linear sequence of nucleotides in DNA. Each molecule of DNA is a double helix formed from two complementary strands of nucleotides held together by hydrogen bonds between G-C and A-T base of operations pairs. Duplication of the genetic information occurs past the use of ane Dna strand as a template for germination of a complementary strand. The genetic information stored in an organism's Dna contains the instructions for all the proteins the organism will always synthesize. In eucaryotes, DNA is contained in the cell nucleus.

Source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26821/

0 Response to "If One Strand of Dna Molecule Read Accttgac"

Postar um comentário